Popular Myths about the Siege of Budapest

- 1) Was Budapest liberated?

- 2) Did the Russians intend to preserve Budapest?

- 3) Was the siege of Budapest "Stalingrad on the Danube"?

- 4) Did the Russians besieging Budapest have multi-fold numerical superiority?

- 5) Did the Russians sustain terrible losses during the siege of Budapest?

- 6) Did the Russians lose about 200 tanks during the storming of Budapest?

- 7) Karl Pfeffer-Wildenbruch, the head of the Budapest garrison, was a poor commander?

- 8) Was the Budapest Operation conducted flawlessly by Marshal Malinovsky?

- 9) In mid-January 1945, the besieged garrison could be saved and only Hitler's stupid no-retreat order denied it salvation?

- 10) If the German relief forces still managed to reach the city, would this have brought salvation not only to the besieged garrison but also to its population?

- 11) The Russians have long claimed that the Budapest garrison numbered 188,000 men. How did they get to these numbers?

- 12) Did General Schmidhuber save the Jews in the Pest ghettos?

- 13) Did Marshal Malinovsky hate Romanians?

- 14) Did Marshal Malinovsky really allow his troops to plunder the city for three days after taking it?

Budapest, 13 February 2020. Speech at the Symposium on the 75th Anniversary of the Siege of Budapest

This year we commemorate the 75th anniversary of the end of World War Two. It is certain all countries involved in the worst conflict in human history will pay tribute to it in one way or another. The interest towards the war, and especially its legacy, hasn’t died down. Just the contrary, there are many signs it is on the rise. There are several reasons for that.

The first (and the most important of them) is that unlike all previous armed conflicts that have left a mark in human history, World War Two continues to be, above all, a political, rather historical event. There are still witnesses and participants alive, the deprivations and adversities have left a lasting mark in the history of many families all over the world, let alone that a considerable number of them have sustained material losses. On top of that, the feeling of pain and the emotion of damaged national honour still impact the lives of many people.

The other reason is the world we know and live in, has been shaped to a considerable degree by the war. The United Nations, the internationally recognized state borders, the spheres of influence, the balance of power in international relations, the European Union, tools for solving conflicts – all of this is a direct result of the lessons learned during the war. The very fact that no new war of such magnitude has broken out in Europe or elsewhere clearly shows the importance of the event.

The third reason is that the war has left behind many unsettled conflicts, smouldering fires and unhealed wounds. Two horrible totalitarian regimes – the German national-socialist and the Soviet communist – swept Europe like giant tsunami and we can still feel the after effects. Politicians are well aware of that, and time and again use World War Two as an instrument for achieving their goals. They add insult to our injuries to reach their wicked objectives. Thus, we are deprived even of our original right to leave the past alone. We are repeatedly bombarded by round- and semi-round anniversaries, monuments are unveiled, celebrations are set up, demonstrations are organised, TV shows are aired, books are published and goodness knows what else is stuffed into people’s minds. Thereby, World War Two has become a gigantic beast that constantly pursues us, and our own notions of the past have become the fuel that gives energy to that beast.

* * *

How do historical myths arise? In many ways. Some of them, no doubt, are launched by politicians. They reach us through media controlled by them, which restlessly and shamelessly reproduce them. And as it is known that when a lie (or half-truth) is repeated many times, it gradually becomes true. Very often we witness how politicians set some groups of society against others using past events, the interpretation of which is still contradictory and controversial. Often these disputes and conflicts are transferred to the international level, poisoning interstate relations.

Another part of the myths are created by those who should debunk and correct them – historians and researchers. Here things are a bit more complex and complicated and it is not so easy to give a more general explanation of why this happens. Sometimes historians create myths unintentionally – in the years immediately following a given event, many documents are usually inaccessible and people dealing with analysis and summaries are forced to rely on personal impressions and opinions of eyewitnesses. That is why we should be lenient with the works on World War II written, for example, in the 1950s and 1960s. However, we must be extremely critical of these authors, who nowadays, with all the abundance of documents and reliable sources, continue to rely on outdated publications. They often do this out of laziness, the pursuit of quick fame, or financial gain with minimal effort. It is even worse when historians place themselves in the service of a political regime or party. They often deliberately distort, manipulate or ignore historical facts in favor of these forces. Such, for example, are many of the so-called official historians in present-day Russia.

A third part of the myths are created by those who usually “consume” them – the ordinary people. Very often, the population of a city or area in which a significant historical event took place has no other way to explain what is happening (or what happened) and therefore create their own versions and interpretations. Often these myths and legends are very enduring, passed down from generation to generation. It is here historians must come to the fore and do everything possible to correct these myths and ideas, because they are the “weak” spot in people’s minds, which is often exploited in the ugliest way by politicians and their entourage.

* * *

Let us now try to identify the most popular and enduring myths associated with the siege of Budapest. Some of them are better known locally (among the Hungarians), others are more popular outside Hungary. I will not share them below, but will grade them according to my own criteria.

1) Was Budapest liberated?

This is undoubtedly a very complex question that does not have an unambiguous answer. Technically, the city should be considered liberated by the Red Army, because this put an end to the fighting in the area and the population no longer risked suffering from hostilities. This is especially true for the thousands of Jews locked in the two ghettos or hiding from the Nilashist gangs. On the other hand, the liberation of the city itself did not bring freedom to its population, because communist terror gradually began, which continued with increasing force in the following years. In this case, the term “liberation” was not very appropriate. I do not undertake to give a definitive opinion on the subject because it is very complex, but I always avoid using the word “liberation” when I mention the territories outside the borders USSR conquered by the Red Army orally or in writing. In such cases, I quote the Dutch author Perry Pierik, who wrote more than 20 years ago that the liberation of Budapest lasted only a few minutes between the withdrawal of the Axis troops and the arrival of the Russian troops. One can hardly find a more appropriate allegory for the events in the Hungarian capital 75 years ago.

2) Did the Russians intend to preserve Budapest?

This myth was quite popular during the Soviet era and is still exploited by historians who sympathize with Putin’s rule, as well as by public figures and writers/journalists. Their claim is usually that efforts were made to preserve the most important buildings, that there were lists of sites that had to be protected, that artillery and aircraft were almost unused, and that casualties among Soviet soldiers would have been much lower if these instructions were not issued. In fact, this is nothing more than another Russian/communist myth about the good Soviet liberator. Stalin’s orders of late December 1944 stated that artillery must be used in the most effective way to destroy enemy garrisons stranded in various parts of the city. Reports of used ammunition show that an exceptional number of shells and mines were fired during the siege. Air force reports and analysis show the bad weather was the only obstacle preventing the Soviet pilots from dropping more bombs and missiles on the city.

3) Was the siege of Budapest “Stalingrad on the Danube”?

The siege of Budapest was often compared to the battle of Stalingrad. This comparison, however, is quite incorrect. The Battle of Stalingrad, as we know it, practically ended when Paulus’s army was surrounded. It was fought with such ferocity, because both sides were able to bring a significant number of reinforcements, weapons, ammunition, fuel, food, etc. to the city without any problems. The same applies to the evacuation of the sick and wounded. At the moment the German forces were surrounded, the main battle was already being fought on the distant “outer” front, and in Stalingrad there were only occasional local clashes. In Budapest, however, the situation was quite different – until the beginning of the siege, the main fighting took place outside the city. When the garrison was surrounded, it quickly depleted available fuel and ammunition, and the evacuation of the wounded was virtually impossible. As early as the beginning of January 1945, the battle became extremely one-sided. The Russians used all available means, especially large-calibre artillery, while the Germans and Hungarians responded mostly with machine guns, rifles, submachine guns, and other light infantry weapons. There is hardly a better example to illustrate this one-sidedness than the fact that in January and February 1945 the entire artillery of the defenders fired no more than a few hundred shells and mortar rounds a day, which was the average daily consumption of one Soviet artillery regiment. We can safely say that soon after its beginning, the siege ceased to be an integrated battle and disintegrated into many small battles, in which the defenders hid in basements and apartments, defending themselves with small arms, while the Russians tried to blast them out with heavy artillery used at close range.

4) Did the Russians besieging Budapest have multi-fold numerical superiority?

This is also a very common myth that has gained popularity mainly due to the fact that until recently, it was very difficult to find reliable information about the numerical strength of both sides. In fact, the difference between the attackers and the defenders was not so great. At the beginning of the siege, the city was defended by about 100,000 Germans and Hungarians, against almost 160,000 Russians and Romanians. As the battle progressed and the defensive perimeter of the defenders shrank, these numbers gradually decreased. By the end of the battle there were approximately 20,000 Germans/Hungarians against 40,000 Russians. To this we must add the little-known fact that up to 25,000 Hungarians were forcibly mobilized by the local Nilashist authorities in the course of the fighting. Presumably, this was an act of utter despair rather than a reasonable measure.

The quality of the opposing forces, their morale, and the tactics used by them played a much more important role than the particular numbers. The quality of the defenders, for example, varied greatly – from very valuable units, even elite, to absolutely useless and uncontrollable detachments of the local Arrow-Cross militias. Adding to this the low fighting spirit of some of the combat formations, as well as the great difficulties with supply, we understand that when it comes to battle the ratio of forces is much more than numbers.

Many may be surprised, but in some sectors the defenders even had a numerical superiority over the attackers. This is because the Russians relied mostly on concentrated firepower. Most of the divisions storming the city were thrown into battle on the move, without a break for recuperation, and their infantry (on paper – 9 battalions) was gathered in no more than 5-6 reduced strength battalions. (In some divisions the effective infantry was gathered in three battalions, i.e. one battalion per regiment.) The lack of infantry was compensated by reinforcing the battalions with many heavy weapons. In most sectors, quite curiously, small infantry companies (20-30 men) were supported by 10-12 cannons and mortars. It is in such cases that factors such as fighting spirit, morale, experience, and good supply come to the forefront.

5) Did the Russians sustain terrible losses during the siege of Budapest?

This is another myth that became widespread after the war, and strangely enough, it is supported by some Russians. (Some publications mention figures of up to 80,000 killed.) The actual losses of the attackers were many times lower, about 9,000 killed and approx. 35,000 wounded. There are mostly two reasons for this – the attackers had well-established tactics for street fighting and the defenders were critically short of ammunition.

Often in books, movies and publications we can read, see, and hear about the so-called “human waves” of attacking Soviet soldiers, ruthlessly driven forward by commissars with pistols in their hands, which moments later were mercilessly cut down by German machine guns. This, of course, is just a myth that should not be portrayed even in Hollywood movies. In fact, in Budapest, the Russians did not need to do this. Firstly because, as we have seen, they did not have enough men, and most of all because they had a well-established and effective street fighting tactic – that of the assault groups. This tactic was first widely used in Stalingrad and then gradually and continuously improved.

What is an assault group? A small number of soldiers (5-20) armed for close combat (submachine guns, grenades, pistols, knives and even sharpened shovels) and tasked with capturing a key object (residential building, house, etc.). Depending on what the object looks like, the group is further reinforced with cannons, mortars, sappers with explosives, flamethrowers, and even tanks. Preliminary reconnaissance of the object was very important, as well as the fact the groups did not have a permanent composition, i.e. they were formed depending on what exactly was to be attacked (i.e. according to the specific task). The assignment was always the same: the group was to sneak unnoticed to the object and then to attack from where it was least expected, often from several directions at once. The actions of the assault groups proved so effective the Russians formed them not only for street fighting, but even when they had to attack bunkers in the field. Of course, the Russians were not

the only ones who employed battle groups, the Germans also used them since the First World War, as did the other participants in the battle for Budapest, the Hungarians and the Romanians.

We mentioned above the losses of the attackers. Two facts deserve additional scrutiny. First, a significant number of the above-mentioned Soviet losses (up to 20%) belong to the artillery branch. Why? Because cannons were often the only way for attackers to deal with solid buildings. They were brought very close to the target (100 m or even closer) to fire at it directly. In this way, they instantly drew the fire of the defenders, and this led to inevitable losses. The other fact to mention is that Soviet doctors and medical staff had to treat a significantly higher number of injuries than before. The reason for this is the environment in which the fighting took place – destroyed buildings, bumps, falling walls, crater holes. This led to abrasions, bruises, sprains, and broken limbs.

6) Did the Russians lose about 200 tanks during the storming of Budapest?

In fact, the AFV losses of the Russians during the street battles (including the engagements in the suburbs) were many times smaller – no more than 49 tanks and self-propelled guns. This is because the Soviet troops operating in Hungary at that time had a very small number of armored vehicles themselves. The losses on the battlefields were very great, neither Soviet industry nor American supplies could compensate for them, so Moscow decided to give full priority only to the fronts advancing on Berlin, and all other formations were forced to settle for the bare minimum. In fact, the Soviet generals leading the siege would have been very happy to have more tanks at their disposal, because there had always been more progress in those sectors of Budapest where tanks were used.

7) Karl Pfeffer-Wildenbruch, the head of the Budapest garrison, was a poor commander?

It is difficult to say where this myth originated, but other German officers and generals who fought in Hungary, as well as some Hungarians, made a significant contribution to its spread. Certainly, Pfeffer-Wildenbruch was not a very pleasant person. He sent some deliberately inaccurate reports to the German High Command, told some lies during his interrogations by the Russians, behaved arrogantly towards the Hungarians during the siege, and proved to be a complete coward during the attempt to break out of the cauldron on the night of 11/12 February 1945. All this does not make him a poor commander. On the contrary, his performance as a combat commander is more than impressive. First, it should not be forgotten that Pfeffer-Wildenbruch was involved in the design and construction of the Attila defensive line, which held the Russians on the outskirts of Pest for nearly two months. In addition, during the battle for the city itself, he did not for a moment let the garrison be fragmented into parts (as planned by the Russians) and all the time managed to conduct orderly retreats; first from the outskirts of Pest to the downtown, and then from there to Buda across the bridges. At the same time, he was fully aware that Buda must be held at all costs, because it was the only point from where a breakout could be launched. His tactics for street fighting were also very correct – instead of counting on passive defence, he relied on repeated counterattacks, thereby significantly slowing down the Soviet offensive.

8) Was the Budapest Operation conducted flawlessly by Marshal Malinovsky?

Malinovsky was usually exalted to the skies by Soviet, and then Russian propaganda, called the liberator of Budapest and whatnot, but in fact he was probably the most incompetent front commander in the final campaign of the Red Army in Europe. Malinovsky disregarded such fundamental principles of the art of war as the creation of shock groups, and very often the objectives he assigned to the armies under him were absolutely unrealistic. Suffice it to say how idiotic was his first plan to capture Budapest in early November 1944. He intended to break into the city by direct assault, to move with tanks along the main boulevards, and to capture Pest within a day, and then to enter Buda over the bridges. The orders sent to the troops during the storming of the city were also unrealistic. He repeatedly demanded Pest to be captured within a day, although there were no conditions for that. Today, it is difficult to judge how realistic it was for Budapest to be captured faster than it happened in reality, but it is safe to say that the Soviet commanders were full of unrealistic expectations.

9) In mid-January 1945, the besieged garrison could be saved and only Hitler’s stupid no-retreat order denied it salvation?

A significant number of Western books (especially the ones written or prepared by German veterans) claim that on 11-12 January 1945, during the Konrad 2 relief offensive, the besieged garrison could have been saved. Let’s recall the events: a small German forward detachment sneaked from Esztergom to the southeast and reached a point about 20 km northwest of Buda. Then Hitler intervened and stopped the attack. However, a careful study of the documents shows his decision was generally correct. First, the orders were not to save the garrison, but simply to open a supply corridor, while the garrison itself was to remain in the city.

Second, the corridor was extremely narrow, and even if the detachment had managed to reach Buda, it would have had to guard two overstretched flanks, each of which would have been up to 40 km long. It would not be a problem for the Russians to cut this corridor for good. And it should not be forgotten that at that

moment the garrison of Budapest was deployed simultaneously in both parts of the city. That’s to say, even if an attempt had been made to withdraw, the defenders would have to be evacuated from Pest over the bridges first, and only then would have moved up the corridor.

In addition, recently declassified Russian documents show that the detachment had zero chances of reaching Buda from the northwest. Literally on every kilometer of its potential route, a solid Soviet defensive position had been built, not to mention that on Stalin’s orders one tank- and one cavalry corps had already been transferred to the German breakthrough zone. It is true the terrain in this part of Hungary was highly mountainous and not suitable for tanks, but at the same time, the columns moving along the corridor would be easy targets for Soviet cavalry, artillery, and aircraft.

Against this background, the claims of the Hungarian historian Ungvary published in the late 1990s that Malinovsky was inclined to allow the besieged garrison to escape, thereby putting to an end the battle for Budapest, sounds rather absurd. Here, we must recall the fact that at that time it was Tolbukhin who was in charge of the Buda sector, not Malinovsky. Apart from that, the documents show that from the very beginning of the street battles, the Soviet command took into account the possibility of an enemy breakout attempt and took the appropriate measures. These included building blocking positions, creating tactical reserves to counter the breakout, as well as planning various countermeasures. Finally, we can only imagine how strong Stalin’s anger would have been if the garrison had managed to escape. I leave the possible reactions of the dictator to your imagination.

10) If the German relief forces still managed to reach the city, would this have brought salvation not only to the besieged garrison but also to its population?

Probably many Hungarians then and now have thought that a possible German military success (be it only temporary) would bring partial or complete deliverance to the local population, but this is just a naive illusion. Germany’s plans in this regard were appalling. Under the instructions of Hitler and Guderian, General Wohler (the commander of Army Group South) intended to build a defensive line on the western bank of the Danube and bring to Buda powerful weapons for urban combat – explosives, flamethrowers, King Tiger tanks, assault guns, and even the terrifying 600-mm “Karl” mortar. We can only guess what Budapest would have looked like if these plans had come to fruition. Most likely, after the war, it would have resembled war-ravaged places like Verdun, Warsaw, Stalingrad or Monte Cassino. Understandably, the Hungarians wanted to feel protected and understood (in terms of their national cause and ideals), but the bitter truth is that that Hitler, his generals and most of the soldiers didn’t care at all about that (and the documents clearly confirm this).

11) The Russians have long claimed that the Budapest garrison numbered 188,000 men. How did they get to these numbers?

The claim of the 188,000-strong garrison is another enduring myth serving Russian propaganda. It has two components: 50,000 killed and 138,000 captured. The 50,000 -killed figure was completely absurd. Not because it was not possible, but because it was not based on an actual body count, but on the estimates of the Soviet headquarters. Needless to say, during combat it is virtually impossible to assess the damage done to the enemy’s manpower, and therefore none of the armies of the main belligerents bothered to report the enemy’s human losses (usually only prisoners were counted).

The only exception was the Red Army. Its units reported losses inflicted on the enemy firepower every day and usually these were always round numbers, i.e. these were rough estimates at best. These data were then summarized and sent to Moscow. Thus, many unrealistic figures, similar to these 50,000, have appeared in the documents. The situation with the POWs is no less absurd. In Budapest in particular, a large number of civilians (males of conscription age) were recorded as deserters and subsequently reported as prisoners of war.

The absurdity is that on some days, the number of reported “deserters” exceeded that of the regular prisoners of war. It is clear that Stalin needed labour force (the so-called Malenki rabot). But it is quite possible that Malinovsky, in his effort to justify the very long siege, simply overdid it, because his initial reports (from the end of 1944) show a real picture of the number of the besieged garrison (90,000 – 100,000). While those written immediately after the battle speak of a large enemy reserve of many thousands in the center of Pest, which Malinovsky’s headquarters “did not initially know about”. Whether Stalin himself believed this nonsense is a different matter altogether.

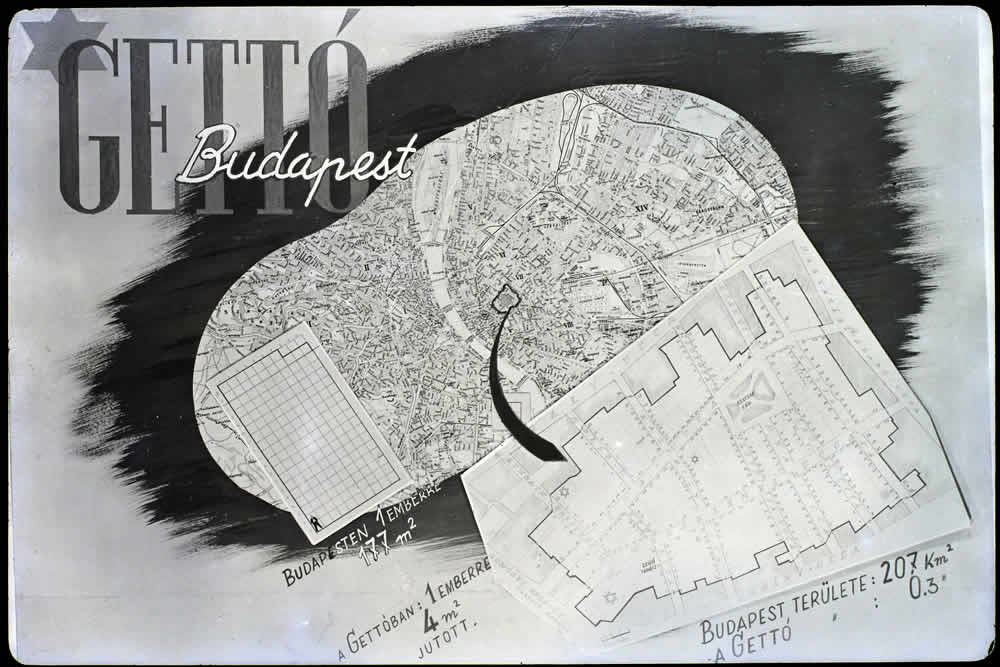

12) Did General Schmidhuber save the Jews in the Pest ghettos?

One of the most difficult myths to refute and explain is that of rescuing the Jewish ghetto in Pest. According to popular legend, in the second week of January 1945, the Swedish diplomat and philanthropist Raoul Wallenberg learned of Adolf Eichmann’s intentions to liquidate the ghetto and contacted the commander of the German-Hungarian troops in Pest, General Schmidhuber, to thwart the plan. Schmidhuber, threatened to be judged as a war criminal after the war, bowed to the threat and agreed to provide security.

This thesis was spread immediately after the war by one of the senior police officers in Budapest, Pál Szalai, and this helped him avoid the gallows. Giorgio Perlasca, another diplomat who helped save many Jews, said he had thwarted the massacre by contacting Hungarian interior minister Gábor Vajna. In both cases, however, there are many unrealistic moments. First of all, it should be borne in mind that at the time described, the greatest concern of the defenders was to evacuate as much of their resources (people, weapons, materials) as possible to Buda, and nothing else concerned them. In addition, in Pest there was a constant shortage of men fit for combat, and everyone who could bear arms was greatly valued.

It is said there were about 70,000 people in the ghetto. How many men would have been needed then and how long would it have taken them to liquidate all those Jews, let alone in a very critical situation? Perlaska’s allegations are also puzzling. It was Ernő Vajna, a high-ranking official of the fascist government, who was in Budapest during the events in question, not minister Gábor Vajna. Didn’t Perlaska really know the difference or did he just mix events from different periods of time?

And last but not least, very few take into account, how short the besieged Axis troops were of ammunition. By mid-January 1945, the daily allotment of ammunition to the defenders of the city was fixed at the miserable pittance of 60 rounds per rifle. No commander in their right mind would spend so much ammunition on such an absolutely senseless, let alone time-consuming task. How many rounds would the killing of about 70,000 human beings require? How many executioners would be needed? How much time would they need to accomplish the dirty work? There are questions that don’t need answers.

The most likely conclusion is that in fact no one had a serious intention to liquidate the ghetto, and even if there were any, it quickly became clear that this would be technically impossible. It’s just that this situation turned out to be very advantageous for many after the war and they did not miss the opportunity to take advantage of it. This, of course, should in no way belittle the merits of the worthy people who risked their lives to save the Jews of Budapest.

13) Did Marshal Malinovsky hate Romanians?

The Romanian 7th Corps fought in Budapest until 15 January 1945, after which it was withdrawn and sent to fight in the forests of the Slovak mountains. Several versions exist as to why the Romanians were withdrawn from Budapest. One of them is that the Hungarians offered much fiercer resistance to the Romanians than to the Russians, and this led Malinovsky to withdraw them. Daily reports, however, show that the number of Hungarian prisoners captured by Romanians is more or less the same as that of Russians. Then this is hardly true. The Hungarian historian Ungvary claims that Malinovsky did not want to share the victory with the Romanians and that’s why withdrew them.

Indeed, they are not mentioned in Stalin’s final order for the conquest of the city, but this was hardly the main motive. Malinovsky himself reports that he withdrew them because they were advancing more slowly than their neighbouring Soviet units. He may have been right about himself, but it should be borne in mind that General Sova’s corps received almost no additional support from the Soviet command (tanks, heavy artillery, aviation, engineering / sapper units), and had to fight its way forward through an area with many factories and solid public buildings, the taking of which required a lot of effort. It cannot be said that the Romanians were weak, because all the documents show that they had high morale, which compensated for the lack of modern armaments. The most likely reason for the withdrawal of the corps is that the Russians thought they would no longer need it in Budapest.

14) Did Marshal Malinovsky really allow his troops to plunder the city for three days after taking it?

This myth is probably the oldest one because it began circulating immediately after the end of the siege. It is also the most difficult to refute because it is of the “urban legend” type. Its emergence should not surprise anyone, because it was probably the way for ordinary Hungarians to explain the predatory behaviour on the part of the victorious army. Wherever we look at it, the very claim of the three days is absurd, because no Soviet division has stayed in the city so long since the end of the battle, and almost all of them had been sent to pursue the escaped remnants of the garrison to the northwest.

As a matter of fact, the lawlessness that brought the Red Army infamy began as soon as they entered Hungarian territory, and the soldiers did not need any special permits to practice it. The statement that Malinovsky would allow such a thing sounds absurd. Those who are familiar with his biography know he was a well-mannered and educated man, and despite his shortcomings as a commander, from a purely human point of view was categorically against such behaviour. Proof of this is the series of orders condemning robbery and violence signed by Malinovsky himself. The lawlessness in question was due to the vicious genesis of the communist system, which produced poor and ignorant people, and not because of the orders or permits of this or that commander.